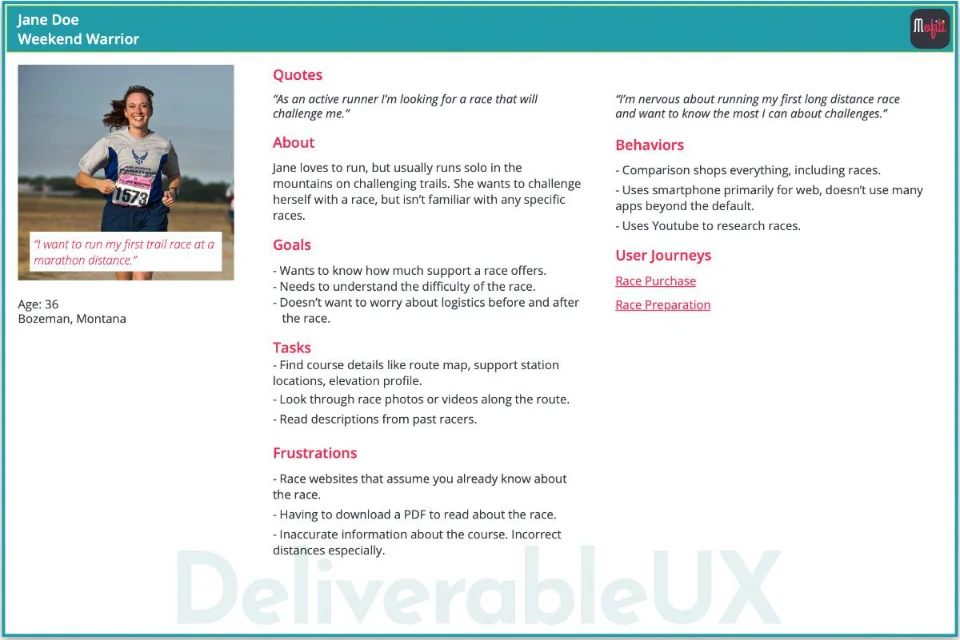

What Should Be in a Persona?

For user experience, personas should be targeted in scope and focus on the why and what the persona is trying to accomplish. The key sections to include in a persona are a Profile, Quotes, About, Goals, Tasks, Frustrations, and Behaviors with a bonus if you cross-reference related user journeys and research.

Wes Hunt

Personas are a Tool

Personas can be an excellent tool in design thinking to build empathy for your users and alignment from your team about users. For UX, a persona does not need to be overly long, only including the details that provide context around the usage of your platform/product/app.

Personas can fail because they include details that don’t help build empathy, provide context, or remind product teams why someone is spending time using their product. They also include too much and are too generic and have unrelated details like many demographics, and stakeholders do not bother consuming the persona.

One example of this is including statistical usage or generic anecdotes that a persona owns a smartphone and a laptop instead of including how they use their devices. I may spend 12 hours a day on my laptop, but it could be a work computer that I don’t feel comfortable using to shop. In my experience, I’ve had personas (based on research) who are very dependent on their phones but only use the default system apps (SMS, Phone, Email, Browser), never installing anything else.

Narrow the focus of the persona to a project and stick to research insights that remind stakeholders of critical behaviors and desires for a user group. Key sections to include are Profile, Quotes, About, Goals, Tasks, Frustrations, and Behaviors with a bonus if you cross-reference related user journeys and research.

Profile

The Profile is the “general” individual section. An image, title of the persona, name, user role, age, and location. The persona title should be brief and descriptive like:

- Busy Business Road Warrior

- The Deal “Researcher”

- Established Neurologist

- Technical Photography Geek

The other details should represent groupings of your users or people you would like to be a customer or user. As with everything in the persona, the profile details should come from user research. For example, pick a location in a region where you have a substantial user base, or want to.

Caution: Avoid using “real” names like those of celebrities and co-workers; you just distract from the goals of the persona. I used to question the usefulness and risks of including too detailed of a profile by causing bias; however, I found that those details can help catch biases early. When sharing your personas with stakeholders that know the customer base, like customer service, they can catch the design/development team’s biased assumptions. If you target college students and all of your personas are in their early 20s, your sales team might call out the considerable group of mid-career or second career students that are usually in their 30s-40s.

Quotes

Quotes are powerful for reminding stakeholders and teammates about the sentiment and emotion the persona represents. Quotes should be from individuals but typify sentiment across the group the persona represents. Include 2-3 statements you encountered during qualitative research (i.e., surveys, interviews).

Some examples:

- “I worry about how much time my kids spend on their phones.”

- “I want my reports to help my team, but they take too long to create.”

- “I’m looking for a position that does meaningful work and also uses my experience.”

About

The About section describes the persona as a person. You can think of it as a summary of all the other sections. If you wrote a summary of a user group that covers their goals and behaviors in general, that would be a good About section.

“Jane loves trail running, and she is very competitive, but has never run a race. She wants to see how she does against other runners but doesn’t have a specific race in mind. She loves technical terrain and would like an “ultra” distance.”

“Juan is an experienced developer who has become bored with his current job. He enjoys the challenge of software programming but feels that he is working with technology that doesn’t interest him anymore. He wants to grow his skills further after 15 years of development yet doesn’t want to leave his job.”

Goals

The Goals section contains the desired outcomes of the user group around the area the project affects. If there are no user goals that affect by the project, then chances are someone needs to rethink the project.

The goals of the user group are the most important and the easiest to get wrong without talking to actual people. When your persona is based on internal assumptions, then your goals show that the most. For most products, the user’s goal is not to use the product. Their goals are something more personal. “Jane” does not use Strava because that’s the outcome she’s aiming; her goal is to become a faster competitive runner. Strava helps her meet her goals by having features that help her improve her performance.

Let’s say you need to improve a reporting tool; some goal examples from users might look like:

- Needs to motivate her department to improve times for KPI X next quarter.

- Wants to know what the worse performing KPIs are so he can make improvements.

Bad examples would sound more like:

- Wants to use pie charts to show more metrics.

- Needs a sort feature on the net revenue column.

Humans don’t care about sort features or pie charts; they care about getting things done. Talk to people, listen to them describe their day and workflows. What are they trying to accomplish?

Tasks

Tasks are the steps people take to meet their goals. Jobs To Be Done (JTBD) also work well as a framework for identifying tasks. Again, just like goals, tasks should be in the users’ own words and based on talking to real people. Have people describe the process they use to accomplish their goals. Have them “think out loud” as they walk you through what they do. Remember, people aren’t actually interested in your product, they’re interested in what jobs your product can perform for them.

Some examples might be:

- Summarize data from our many analytics tools.

- Highlight essential changes from last quarter for the revenue section.

- Pull up last quarter’s report.

- Google for ultra-marathon races in Colorado.

Frustrations

These are problems of users they know about with the status quo or their current workflow. Frustrations are better for us to solve than other problems, because people actually know they have them. Almost the anti-goals section. Frustrations are just as important to capture and get from real users as goals. These will differentiate your solution from your competitors’ the most and are easier to market than problems our users don’t realize they have. Even in a crowded market, you see new solutions succeed because they addressed true user frustrations in the market.

- Can’t find details about parking for the race.

- Doesn’t like giving personal information just to find out how much a product costs when they are evaluating if it even works for them.

- Feels like they don’t own their own data in a dashboard because they can’t export it.

Behaviors

Behaviors are significant because they remind stakeholders of the reality of the user base. How the user group behaves may differ significantly from the other sections that mostly come from users’ “self-reporting” like for Tasks and Goals.

A common mistake in a UX oriented persona is including too many demographics and statistics and no observed user behaviors. Back to the example in the introduction, the statistics around tech usage provides few insights compared to behaviors with tech. An example of this from my own experience is in smartphone use in healthcare. Our statistics showed that 98% of our users’ used smartphones and about 2/3rds were iPhone users versus 1/3rd Android. Although that is useful information in general, it doesn’t tell the whole story. When observing clinicians using iPhones, it wasn’t uncommon that some had never installed a single application and had never logged into the Apple App Store. On Android, one of the “killer” features is the notification tray at the top that shows app icons that have unseen notifications. I obsessively read and clear them; however, many of our clinician Android users completely ignore the full tray of app icons and notifications. Statistics aren’t necessarily bad, but they do not show anywhere close to the full picture to make sound product decisions.

Supporting Research & Work

The Web was built at CERN to link together resources for researchers. Linking data together has apparent advantages over static paper documents. It is time UX designers embrace this now old standard and stop making “flat” personas and other UX deliverables. Your personas should enable stakeholders to dig into how you came to the insights you did. Be transparent; don’t hide your hard work. What journey maps use this persona? What assumptions were made to build the persona? A good persona summarizes user group details in a way that stakeholders can quickly make decisions, but should still enable consumers to dig into the specifics if they want.

At a minimum, we like to connect our personas to any user journey maps, research projects, and any diagrams we created to develop the personas, like affinity diagrams.

Conclusion

These sections are what we use in our personas based on experience. Over the years, I have added or removed some sections based on what seems to provide the most benefit, but this is still mine and some others’ opinions.

Further Reading

- “Inmates Are Running the Asylum – Chapter: Designing for Pleasure” by Alan Cooper, we believe is where personas were first introduced.

- “Lean UX: Proto-Personas” by Jeff Gothelf, Josh Seiden

- “User Experience Mapping: Personas” by Peter W. Szabo