What Is an Experience Map?

An experience map represents the big picture of all the different paths all users take to reach their goal. Experience maps help companies see possible pain points for users in a specific domain and where improvements are needed to create a strategic advantage. Because this UX map type improves design thinking around complex ecosystems without being limited to specific solutions, it helps identify advantages that are missed by featured focused thinking. This guide is an exploration of experience maps when to use them, who they are for, and how to create them.

Wes Hunt

What exactly is an experience map?

An experience map is a representation of all the complete (end to end) activity any user takes to reach a specific goal. Experience maps should be product agnostic and primarily focus on all users and all end-to-end routes and how they reach a goal with or without any services, different from a journey map. The experience map shows the questions, the answers, the paths, the emotions, behaviors, pain points, and feelings someone goes through.

An experience map is just that, a map of the experience reaching a goal from start to the goal state. Imagine mapping out one of your experiences, like planning a trip for your family, or looking for a new job. Using sticky notes or on a whiteboard, the full experience mapped can sometimes be vast, over 4 feet wide, showing every possible path to get from start to finish. The map may include several services or none for the user because people usually do not focus their experiences on a product.

One note, before launching into this guide. It is only a guide, not a rulebook. Although we base this on our own experience in UX/HCI and from consensus across trusted UX experts, there is still a lot of confusion out there. Tough for a novice, but not necessarily a bad thing. As you gain experience, you should focus on what tool and configuration are best for the current challenge at hand. What serves the user and reduces the risk for your team the most? If that means some hybrid experience/service/journey map is best, then rock on!

What is the difference between a customer journey map and an experience map?

As mentioned above, experience maps are often confused with customer(user) journey maps. They are equally useful UX maps, but each is for different challenges and research. Unlike experience maps, customer journey maps are usually not product agnostic and primarily focus on a single persona and how they reach a goal with a single service or product. Again, an experience map is for general human activity going through a specific experience that may cover multiple products or no products at all. You can create user journey maps to describe how your product is going to target specific opportunities identified in the experience map for your target users.

We will cover user journey maps more in-depth in a separate article, and why we prefer to call them user journey maps and not customer journey maps, it’s a big topic.

Who is an experience map about?

Experience maps are about current customers, possible customers, or any person who is trying to reach the same goal you are building. Most UX maps have this in common, but what’s different about experience maps is they are for all users trying to reach a goal or going through an event.

Elements that Makeup an Experience Map

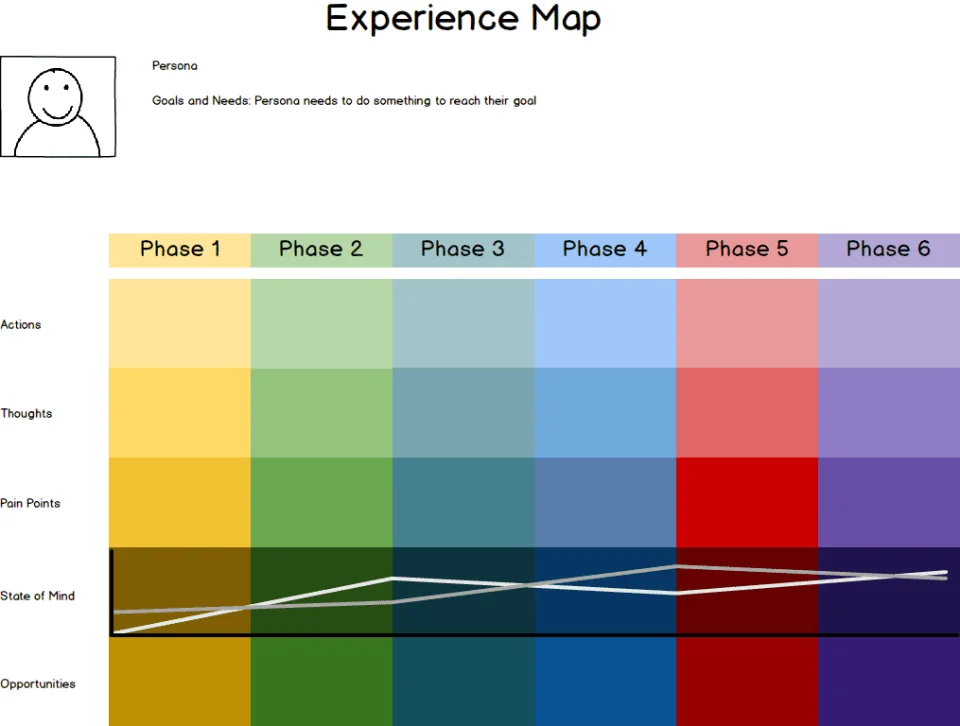

Although experience maps are flexible, and you should only include details that best tell the story of the experience, there are some common elements that you can choose from:

Stages/Behavioral Phases

If you think of an experience map in terms of a grid layout, the phases would be the columns that everything else applies too. These are similar to stages in a service blueprint or journey map. The difference, though, is we are focusing on the user’s motivations and their changing behavior. External or internal factors cause a phase in the experience, but the factors should include all the major external factors, not just the ones from your service. Here are some examples:

- Months and trimesters of pregnancy.

- The phases of fitness levels leading up to running a marathon. Phases: deciding to race a marathon, running a 5K continuously, maintain an 8 minute/mile pace for 13 miles.

- The stages from knowing you need a new car to buy a specific car model. Some phases: not interested, start looking, researching brands, research models, visit dealerships, purchasing.

With each one of these examples, it would be naive to think one product would be a single influence for almost any related phases. For buying a car, the first phase of deciding to research cars could be caused by competitors’ reliability issues. The consumer will be likely to have been influenced by lots of different media and comparison articles that make them fearful or confident in specific brands.

Goals and Needs

What is the person trying to accomplish? In any UX map or task, user goals and pain points should be the first questions in mind. Everything else flows from those two elements. Again, these are strictly from users’ experience. A user has the goal of easily creating professional-looking reports, not to use X product.

We prefer to identify user goals, but sometimes a user does not have a specific goal. In this case, defining a need is more useful. For an experience map, a need is often caused by a phase.

Actions Taken

Again, actions taken focus on the persona or role. What activities do they take during a behavioral phase that is in reaction to that phase? What actions caused the phase? In the car buying example, do they watch Youtube reviews and read articles from specific media? Do they ever go to a dealership in a phase before the purchase phase? For the pregnancy example, what actions does the expectant mother take in reaction to being in the 2nd trimester?

Actions taken also include the service touchpoints. Is the person reaching out to a service, using some product?

Thoughts or Questions

What is the user thinking at this phase in the process? Do they have questions that need answering? The marathon trainee may have questions about nutrition for training, race day, or training recovery. Thoughts could be quotes from your user research or diary studies. “I want to avoid dealing with car salespeople.”

State of Mind

The state of mind is usually the emotional or intellectual state at the specific phase of the experience. Is the user angry, frustrated, confused, curious, indifferent at this point? What is their overall sentiment about this phase?

Pain Points

What are the experience gaps for the user, if any, in a phase? Are there challenges in the current ecosystem of services that cause frustration or require work arounds from the user? These should be related to any goals or needs identified for the phase. There isn’t always a pain point, and that’s just as important to know. Are stakeholders in your company, focusing on a feature that does not solve pain points for users? As always, these pain points should be from the perspective of the persona. You may perceive that something could be better, but if it’s not blocking a user goal/need, then it’s not a real pain point. Save your perceived pain points for the next section.

Opportunities

Opportunities are where you identify gaps in the user experience between the goals of the user and any pain points for a particular phase. If stakeholders or teammates are throwing in solution ideas, here is where you would see if the “solutions” actually solve anything for the user. Is everyone obsessed with a specific solution that doesn’t match a goal/pain point gap? Is there a massive gap that no one in the industry is addressing or they are causing?

What do you need for an experience map?

Research Insights! You need to know what your user group or target user group is experiencing. Some of the experiences you may know of if it is a personal pain point. However, as with any other product validation step, the goal of an experience map is to describe actual evidence of real experience and any real pain points a group is going through. Your personal experience is a hypothesis that requires proof from user research.

For any UX deliverable or other UX tools, these will be nearly the same. Goals, Qualitative & Quantitative Insights, and overall Insights. Just tattoo that on your arm now, so you don’t ever forget.

Where to get data for an experience map?

You find data for your maps in many places, including logs, analytics reports, customer surveys, interviews, reviews, testimonials, forums, or conversations with customers and potential users. Experience maps should include information from both employees and customers; observations, marketing, customer, and competitive research data are all excellent sources.

Quantitative Insights

Quantitative insights come from any sources that provide numerical data, for example, surveys and analytics. Quantitative research helps identify and validate what the touchpoints are for experience and sentiment during different phases. With analytics, you can show what percentage of people use a specific touchpoint, or have a particular experience (6% of men are color blind in the US). With quantitative questions in surveys, people can rank their sentiment during a phase.

“From 1 (Happy) to 10 (Angry), how did our customer support make you feel?”

Qualitative Insights

Insights from qualitative research will answer important questions about the Why of experience in each phase. Interviewing people to find out what they are doing, what they are thinking, and what they are feeling during each specific phase enables the UX designer to deliver insights so stakeholders can understand and evaluate any opportunities to better serve customers. For example, if many people have a process not meant for a specific goal, but are both confident they can complete a task and are happy with the outcome, then there probably isn’t much opportunity for that phase.

Overall Insights & Takeaways

From Adaptive Path:

“The map is supposed to be a catalyst, not a conclusion.”

This point is essential for all of UX. Even if the insights are not what you were hoping for, as long as it is a catalyst for decisions in the next phase of your product strategy, then the UX work succeeded. Whatever tool or process you use, it should be driving informed change to serve the customer and business better.

When to use an experience map?

Hypothesis and user research are the only prerequisites. An experience map is useful during any part of the development process, but earlier is better. You should map the experience sooner rather than later, and it will be priceless for finding problems to solve. Finding problem areas before fixating on a solution or implementing yet another poor feature will prevent wasted time and resources. Because the experience map is a beautiful way of showing actual customer experience throughout a specific process or domain, they help find additional opportunities an existing feature can address and avoid adding “solutions” to experience without problems.

The other criteria for deciding when to use an experience map depends on how complex the problem space is. Versus other map types, the experience map is especially powerful for complex ecosystems and experiences. For simpler experiences with few touchpoints and fewer personas, there might be better tools to use.

Who is an experience map for?

The whole team! Experience maps show business stakeholders more details about the diverse paths a customer can take and where there are pain points and possible opportunities. Because this map type is excellent for describing complex problems and domains, it is an excellent catalyst for discussing opportunities with stakeholders. These can be stakeholders or teammates from any part of your company. Good experience maps will be self-explanatory and can stand on their own. Because of this, they are also suitable for “passing around” to build alignment and understanding with other departments.

Who creates an experience map?

Anyone can create the map, but you need to include the UX researcher role. Insights gained from usability studies, diary studies, survey results, and user interviews should inform the experience map creation, so the person doing user research should be directly involved in creating the map. Experience maps do not need intricate designs, or visual design skills to produce, so it does not require a designer. Ensure people from every department of the company are a part of the process. Especially anyone that interacts with the customer at any point in any way.

Why create an experience map?

To improve the customer experience, of course! Happy customers are more likely to come back. A good experience helps the customer finish the path to your business goal, i.e., make a purchase. Create experience maps at any time, even before the product design is started! How great would it be to build a product people love because it fixes real pain points? As mentioned above, these maps excel at tackling complex domains, distilling how users behave and finding pain points when trying to meet a goal in those domains.

Advantages and disadvantages of an experience map?

There are many advantages to using experience maps, but let’s start with some dangers:

- Too much information: Every possible path with thoughts and emotions can be very overwhelming, confusing, and hard to follow.

- Overdesign: All maps share this one, but because of the amount of possible information, it is easy to focus too much on the visual design and to come up with a unique look instead of something readable, understandable, and usable.

- Too broad: It is an overview of the whole process and might not be detailed enough for specific needs. You may need to bring in journey map aspects or use another map for describing simpler processes.

- Too abstract: If you lack enough supporting data, stakeholders may not trust the insights. You need to call out assumptions and provide supporting research for everything else. Linked map systems are much better at conveniently providing access to research insights.

- Too narrow: Too much detail can create analysis paralysis and mapping overload. It also makes the map harder for stakeholders to independently consume.

- Lack of customer access: You do not have all the needed information. In siloed organizations, you will not get input from all sides or all departments of the company, especially ones that work with the customer in any way. That can kill the success of the mapping project and the potential for useful insights.

Some advantages we like are:

- Emotions are in focus: Product teams forget to connect with the people using their applications. Including emotions is key to a good experience and building empathy.

- Flexible: Experience maps can include products, or be purely user perspective centric. Nothing makes stakeholders take notice than realizing people do not even think about their latest features or use a competitor to fill in your gaps.

- Covers many paths: One experience map can cover multiple potential paths at once for many users.

- Exposes pain points: Experience maps and service blueprints are our favorites for uncovering unknown pain points and potential strategic advantages.

- Simplifies complexity: We included this before, but this is our favorite. Experience maps explain complex problem domains in a simple, visual manner.

Further Reading and References

- “Mapping Experiences Chapter: Experience Maps” by Jim Kalbach, O’Reilly Media

- “UX Mapping Methods Compared: A Cheat Sheet” by Sarah Gibbons at Nielson Norman Group

- “Getting started with User Experience Mapping” by Peter W. Szabo

- “The Anatomy of an Experience Map” by Adaptive Path

Taxonomy:

ux maps